“No, I’m not on a scholarship from Africa“; “Yes I do have the right to be offended when you confuse me for the only other black girl in my year“. These were some of the captions on white boards held by Oxford University students last week as part of photographic and social media campaign to draw attention to racism among students at the elite University. The campaigns ‘I, Too, am Oxford’ and ‘I, Too, am Cambridge’ were inspired by students at Ivy League universities in the United States.

It all began on the 10 February 2014 with the release of a video called 33 by students at the School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles (Why 33? There are 33 black students out of about 1100 at the School). A young woman speaking directly to camera tells us:

“I agreed to participate in this awareness campaign because I am so tired of being on this campus everyday and of having to plead my humanity essentially, to other students.“

The video records student stories of the bold and the viscous qualities of everyday racism on the campus. When topics of race and gender come up, all eyes can turn to the student of colour, who in those moments feels that she carries the burden not of learning but of teaching.

There is the touching of hair, the comments about speech “You don’t sound black“, the feelings of not belonging; grinding loneliness and insecurity. “It’s so far from being a safe space. It almost feels like that staying at home would be better for my mental health, my self, than being at class.”

The video conveys experiences that are often too difficult to put into words and which academics can have only a peripheral contact with — how racist atmospheres and cultures can build up and take hold in the classroom, the corridors, the cafes and bars. What is unsaid, but which haunts the video, is the long-term emotional and educational costs of such formative experiences.

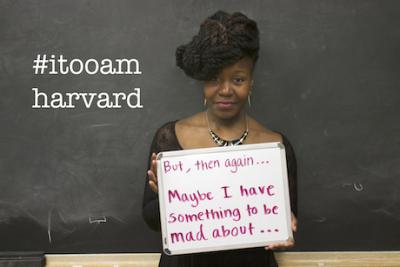

33 was followed last month by a campaign posted on a Tumblr blog ‘I, Too am Harvard’ — a homage to the poem ‘I, Too’ by Langston Hughes.

The campaign developed from 40 interviews with Harvard students. The interviews were collected and used in the making of a play about campus racism by an undergraduate student, Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence, for the University’s annual Black Arts Festival.

The photographs on the Harvard blog feature students holding up boards with quotations that give a flavour of the types of racism that they face, from resentment of affirmative action schemes to coarse stereotyping – “You’re so lucky to be black … so easy to get into college!“; “No, I will not teach you how to twerk“; “My name is Monica, not ‘My NIGGA’”.

“Our voices often go unheard on this campus, our experiences are devalued, our presence is questioned” the ‘I, Too’ blog states. “this project is our way of speaking back, of claiming this campus, of standing up to say: We are here. This place is ours. We, TOO, are Harvard.”

The interim Dean at Harvard, Donald Pfister, was quick to send an e-mail to undergraduates supporting the campaign and the opportunities it opened for conversations about racism.

In Oxford, events took a very different turn last week. Perhaps it was inevitable that there would be some denial and a counter-campaign. But the smearing of Oxford’s ‘I, too’ was not a slick makeover coming from the University’s PR machine. It was something altogether more strange and Orwellian.

Three days after “I, Too, Am Oxford” was launched, gaining widespread and international media coverage, a rival Tumblr blog We Are All Oxford was created. It was a lateral blow, a campaign by fellow students. The blog acknowledges that racism exists at the University and should be challenged, but the ‘All Oxford’ students claim that ‘I, Too’ misrepresents the University.

“We want to show people that many ethnic minorities have an overall positive experience here,” says ‘All Oxford’. “We want to show that the university selects on academic excellence and actively tries to attract people from all walks of life.”

While mimicking the visual branding of the original “I, Too” initiatives, ‘All Oxford‘ features an array of students and issues. One white-board declares that “Our JCR’s (college student bodies) have Equal Opps reps: ethnic minorities, LGBTQ, International reps…”. Another board held by two smiling white women informs us “We are from state schools (Can you tell?)“.

In an interview given to Cherwell, the Oxford student newspaper, graduate student Luke Buckley, explained his opposition to “I, too“, drawing upon arguments made by anti-racist scholars and activists. These are arguments that have sought to shake off ideas of absolute (biological) race differences that are a hangover from 19th century race science. According to Buckley, the Oxford “I, Too” campaign,

“…reinforces the very phenomena that it tries to ameliorate. It necessarily implies that there is something common to the condition of ‘being of colour’ which ironically excludes not only people who aren’t ‘of colour’ but also those who are ‘of colour’ but who don’t identify with a similar set of experiences or perhaps feel uncomfortable with the divisive terminology.”

‘All Oxford‘ also trades upon, but distorts, the idea of intersectionality, pioneered by the black feminist law academic Kimberlé Crenshaw. An intersectional approach recognises the continual interplay between identities such as ethnicity, gender, class and disability.

The ‘All Oxford‘ version of intersectionality is just one recent example of how intersectional perspectives are being used to make equivalences between different identities and experiences. In the alchemy of the identity puree that results, racism disappears.

The ugly irony is that ‘All Oxford‘ demonstrates powerfully the types of indolent ignorance as well as the aggression that the original campaigns have been trying to uncover and articulate.

As one of the “I, Too” Harvard boards put it: “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.”

Might “We Are All Oxford” put off some prospective students? I think so.

Figures obtained by the Guardian under the Freedom of Information Act last year revealed that white applicants to Oxford with the same A level grades as ethnic minorities, were twice as likely to get a place on the most competitive courses.

Equalities initiatives and discussions concerning widening access are longstanding concerns, important across the university sector.

These new campus anti-racism campaigns have broadened the focus of attention from admissions to student experience. They suggest that for elite universities, widening access is only part of the problem of tackling inequalities and exclusion.

In their different ways, the campaigns raise the less prominent, but equally important question of what happens to those students from ‘non-traditional’ backgrounds once they enter institutions in which they have previously been marginal?

This is a pertinent question at this time of the increasing corporatisation of universities and where a high premium is placed upon ‘student experience’, as measured through the tightly circumscribed criteria of the annual National Student Survey (NSS) of all final year undergraduates in the UK. The survey attempts to gauge the quality of teaching and learning, assessment and feedback and even library resources. The rating scales do not go anywhere near the matters raised by the “I, too” students. I would imagine that attention to these student experiences might result in a very different ordering of the league tables.

All of us in Higher Education need to reflect upon how racism and other forms of inequality operate within our institutions. We need to support and listen carefully to these brave dissenting voices, not deny or discredit them. We need to learn. We need to do better.